On November 7, 2023, Ukrainian side Shakhtar Donetsk secured a 1-0 victory over Barcelona in the Champions League. The match took place in Hamburg, Germany–nearly 1,500 miles away from Shakhtar’s home stadium in the Donetsk Oblast of Ukraine. Shakhtar haven’t played in their home ground, the Donbas arena, since April 2014, when a Russian militia seized the Ukrainian city of Sloviansk, starting the Donbas War. The Donbas conflict, along with other regional conflicts between Russia and Ukraine, has since grown into a full-scale war between the two countries, with Russia’s invasion in February 2022 leading to one of the deadliest conflicts in Europe since World War II.

Russia’s invasion significantly changed the lives of over 40 million people living in Ukraine. Among them was Taras Stepaneko, Shakhtar Donetsk’s captain. In the immediate aftermath of the invasion, Adam Crafton, a journalist for The Athletic, spoke with Stepanenko, who was staying in an underground shelter with his wife and three children, aged eight, seven, and four. Stepanenko mentioned to Crafton about how he and his family had “woken up to the sounds of bombs” in the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv. Stepanenko’s story was one shared by millions of Ukrainians following Russia’s escalation of its war with Ukraine.

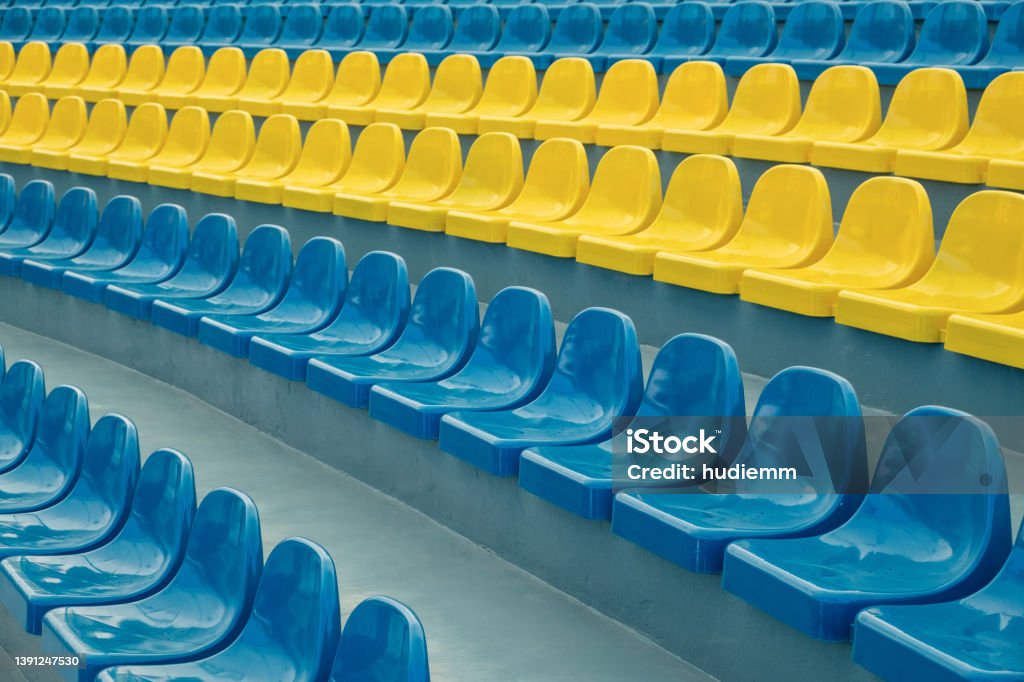

Russia’s invasion occurred in the middle of the Ukrainian Premier League season. Play was halted on February 24, with the season being officially terminated on April 26, 2022. Shakhtar sat top of the table at the time of the war’s beginning, two points ahead of Dynamo Kyiv, but no champion was crowned. Remarkably, play resumed for the 2022/23 season, though the league and its teams faced significant challenges. In the wake of the invasion, almost all of the league’s foreign players seeked to flee the country. This meant that many Ukrainian teams lost some of their best players without any compensation (Shakhtar, along with other Ukrainian clubs, sued FIFA in the Court of Arbitration for Sport over lost transfer fees, though CAS ended up ruling in favor of FIFA). Two teams, FC Mauripol and Desna Chernihiv, had to withdraw from the league due to their stadiums being significantly damaged as a result of the conflict (Mauripol, who had competed in the Ukrainian top flight for five successive seasons prior to Russia’s invasion, have since ceased operations due to the war). No fans were in attendance at any game in the 22/23 season, with bomb shelters and air raid sirens being put in place for the safety of players and staff.

Football in Ukraine has long served to engender national pride throughout the country. The first official match of Ukrainian football is widely regarded to have been held in Lviv in 1894. The game, featuring teams from Lviv and Krakow, was only to be played until the first goal, which arrived just six minutes after kick-off. Despite the match’s brief runtime, football soon took off in the region, and later across Ukraine itself. During the years of the Soviet Union, Ukraine was represented by Dynamo Kyiv, one of the USSR’s and Europe’s foremost teams. Dynamo’s golden era came under the management of Valeiry Lobanovyski in the 1970s and 80s. As a player for Dynamo, Lobanovyski was extremely popular and talented, with Behind The Curtain author Jonathan Wilson writing,“Lobanovyski the player was the image of the dilettante left-winger, taller than most, and slower, but blessed with sublime close control and one of the best left feet the Soviet game has known.” For all his quality, Lobanovyski seemed to lack commitment to the game, retiring at the age of 29 after leaving Dynamo for Chornomorets Odessa and later Shakhtar. As a manager, however, Lobanovyski revolutionized Soviet football. Lobanovyski had Dynamo play a hard-pressing, high-pace system that would come to influence the likes of Jurgen Klopp at Liverpool. Speaking on Lobanovyski’s tactics, Wilson writes, “It is overly simplistic to claim that Lobanovyski and the prevailing ideology turned players into little more than cogs in a machine, but there is no denying that his Dyanmo were a discernibly Soviet side and it is probably not inaccurate to say that they played a Communist version of the Total Football of Rinus Michels and Johan Cruyff.” Under Lobanovyski, Dynamo would win eight Soviet Supreme League titles, six Soviet Cups, and two UEFA Cup Winners’ Cups.

Lobanovyski’s first two spells at Dynamo, between 1973-1982 and 1984-1990, were interrupted by a short stint as manager of the Soviet Union national team. When Lobanovyski returned to Kyiv for a third time in 1997, Ukrainian football had been significantly altered by the fall of communism in Eastern Europe and the country’s independence. While Dynamo benefitted significantly from foreign investment (as well as a golden generation that boasted the likes of Andriy Shevchenko, who won the 2004 Ballon d’Or), their monopoly on domestic football was now challenged by the likes of Shakhtar and FC Dnipro. The rise of money in Ukrainian football also brought with it structural problems. Match-fixing, which was commonplace in Ukraine during Soviet times, became possibly even more prevalent following the introduction of capitalism. Additionally, criminal groups looked to exploit the power vacuum left by the USSR’s fall. In 1995, then-Shakhtar president Akhat Bragin was killed by a bomb that went off in the RSC Olympiskyi stadium, Shakhtar’s home ground at the time. It is alleged that the bombing was carried out by one of these groups, though Bragin’s successor Rinat Akhmetov has been the subject of suspicion regarding Bragin’s death.

The most infamous moment in Ukrainian football, however, occurred in 1942, when Ukraine was under Nazi occupation. FC Start, a squad composed of Ukranian bakers, played Falkef, a team representing the German Luftwaffe, a match Start won 5-0. A replay was scheduled with an SS referee, though Start won the match 5-3. On the game, Wilson writes, “Falkef’s humiliation was compounded when Oleksiy Klymenko, a young defender, rounded the keeper, dribbled to the line, then, rather than score, ran beyond the ball and hoofed it back towards the middle of the pitch.” After Start’s second triumph over the Germans, all eleven of Start’s players were rounded up for interrogation. Ten of the players were eventually sent to the Babi Yar ravine, where the Nazis carried out most of their executions in Ukraine, with the eleventh member, Mykola Korotkyth, being killed after twenty days of torture. The game became the subject of myth throughout the Soviet Union, with some stories claiming that Start’s players were spontaneously shot during the game. The “Death Match,” as it came to be known, is representative of how, in Ukraine, football has continued in the face of turmoil and oppression.

As mentioned earlier, many of Shakhtar’s international players left the club after Russia’s invasion, which left Shakhtar fielding a squad of predominantly Ukrainian players. While Shakhtar has deep historical ties to Ukraine’s working class, having been founded as a team of coal miners, the turn of the century saw the club become a hub for some of the best foreign talent in Ukraine, particularly from Brazil (Frenandinho, Willian, Fred, and Douglas Costa all plied their trade for the Donetsk outfit at some point in their careers). Competing in the 2022/23 Champions League, however, Shakhtar was given the chance to showcase Ukrainian talent to an international audience. After impressing in a group containing Real Madrid, Shakhtar winger Mykhailo Mudryk was sold to Chelsea for around $108 million . While Shakhtar failed to qualify from their group, finishing behind Real and German outfit RB Leipzig, their performances represented the resolve their home nation possessed during the war, despite their “home” games being played in Warsaw. The 2023/24 Champions League campaign, which Shakhtar participated in as Ukraine’s sole representative for the second season running, saw Ukraine’s best footballing moment since the war’s outbreak. In the 40th minute of their meeting with Barcelona at the Volksparkstadion, Danylo Sikan, a 22-year-old Ukrainan forward, barried a header into the top-right of Barca keeper Marc-Andre Ter Stegen’s goal. Sikan’s finish gave Shakhtar a lead they would not relinquish, and a famous win over the five-time European champions. While Ukraine’s football fans watched from a distance, half a continent away in a nation that enters its third year at war, it is hard not to feel that Shakhtar Donetsk, much in the same way FC Start had during Nazi occupation or Lovanovyski’s Dynamo had during Soviet times, were acting as a light in a time of darkness for their country.