Ask anyone about Russian politics, and one name dominates the conversation: Vladimir Putin. Since rising to power in 1999, Putin has reshaped Russia’s political landscape. He has led the country into multiple conflicts (most notably in Ukraine), altered the constitution to extend his rule, and consolidated power across all branches of government under a single dominant party: United Russia.

After President Boris Yeltsin’s resignation in 1999, Putin quickly moved to weaken opposition parties, restrict media freedom, and centralize authority, transforming Russia into what political scientists describe as a procedural democratic system—a system that holds elections, but without real competition. Such governments often aid the presence of authoritarian leadership.

So who stands against Putin today—and what does that “opposition” actually look like?

In June 2023, Western media became enthralled with the Wagner Group—a Kremlin-linked private military force—launching a brief mutiny against Russia’s military leadership. Led by Yevgeny Prigozhin, Wagner troops seized a command center and advanced toward Moscow, halting only after a negotiated deal brokered by Belarus. Though Prigozhin insisted the action wasn’t aimed directly at Putin, the rebellion exposed internal rifts. Two months later, Prigozhin died in a mysterious plane crash, widely suspected to be a Kremlin-orchestrated hit.

Many Americans are familiar with Alexei Navalny, a prominent anti-corruption activist and outspoken critic of Putin. Navalny faced imprisonment and then died under suspicious circumstances in a Siberian prison in February 2024. While the Kremlin claims he died of natural causes, his death has been widely condemned as politically motivated.

Just weeks later, Russia held a presidential election. As expected, Putin won decisively, securing over 87% of the vote in an election widely viewed by international observers as neither free nor fair.

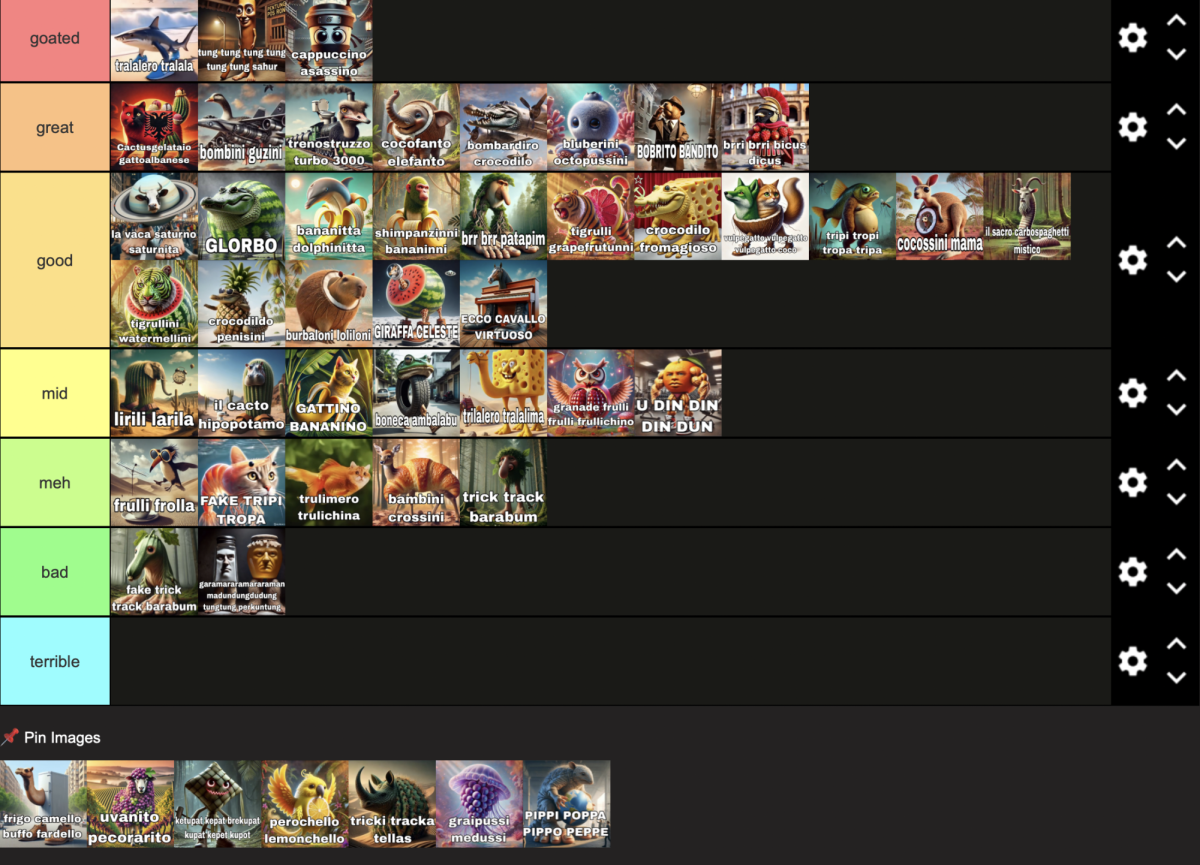

But what may come as a surprise is that the second-place finisher was Nikolay Kharitonov, the candidate from the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF)—a party that many assume faded with the fall of the Soviet Union.

Kharitonov, a longtime member of Russia’s parliament, the State Duma, first ran against Putin back in 2004, when he received nearly 14% of the vote. In 2024, he won just 4.37%—roughly 3.8 million votes. At 75 years old, his campaign was subdued, and notably, he refused to publicly criticize Putin during the election cycle.

This raises a critical question: was Kharitonov truly an opposition candidate, or merely part of a carefully managed illusion of democratic choice?

Kharitonov’s campaign existed as part of a systemic opposition approved by the Russian Central Election Commission. These are campaigns that participate in elections but pose no real threat to the regime. Their presence helps maintain a perception of legitimacy—a way for the Kremlin to claim that Russia remains democratic, even when elections are manipulated and dissent is silenced.

Had Kharitonov posed a real threat to the status-quo, he would have faced resistance from the Election Commission and his life may have been in danger.

While the CPRF still holds seats in the Duma and appeals to some nostalgic for the Soviet era, it operates within boundaries set by Putin’s government. Kharitonov’s support for the war in Ukraine and his unwillingness to challenge Putin publicly suggest he offered voters no meaningful alternative.

Though Kharitonov began his career in the Agrarian Party, which once promoted rural and socialist values, he later joined the CPRF and aligned with many of the regime’s policies. His candidacy, in the context of Russia’s tightly controlled political system, seems designed more to simulate pluralism than to offer real change. Pluralism means that groups within a country compete for influence in the government apparatus and the more successful groups gain greater influence. Such a process may exist in Russia on paper but not in reality.

In the end, Russia remains a highly centralized state where electoral institutions exist in form but not in function. For now, Vladimir Putin continues his decades-long rule. Whether any true opposition can rise in a system so thoroughly controlled remains one of the most pressing questions in global politics. At 72 years of age Putin is eligible to be re-elected again in 2030. If that happens, his legal authority will end in 2036. At that point he will be 83 years old. The questions about Putin’s succession and what a post-Putin Russia will look like will only be answered in time. Tick… Tock…