In September of 2024, Mexico passed a constitutional amendment that would change the judicial system of the country, and seven months later, reactions are still mixed.

The amendment restructures the Supreme Court from eleven to nine judges and reduces their terms from fifteen to twelve years. In addition, judges of all levels of courts will be elected by popular vote instead of appointed. The latter change has proved to be the most controversial, causing protests and strikes among judges across the nation.

Former president Andrés Manuel López Obrador, commonly known by his initials AMLO, introduced the amendment before the end of his term in response to what he believed were actions of judicial corruption. He said that many of his failed reforms, which were struck down as unconstitutional by the courts, were meant to help the Mexican people. Thus, AMLO believes that the best way to combat judicial corruption is through this new judicial reform, and he earned the support of his party.

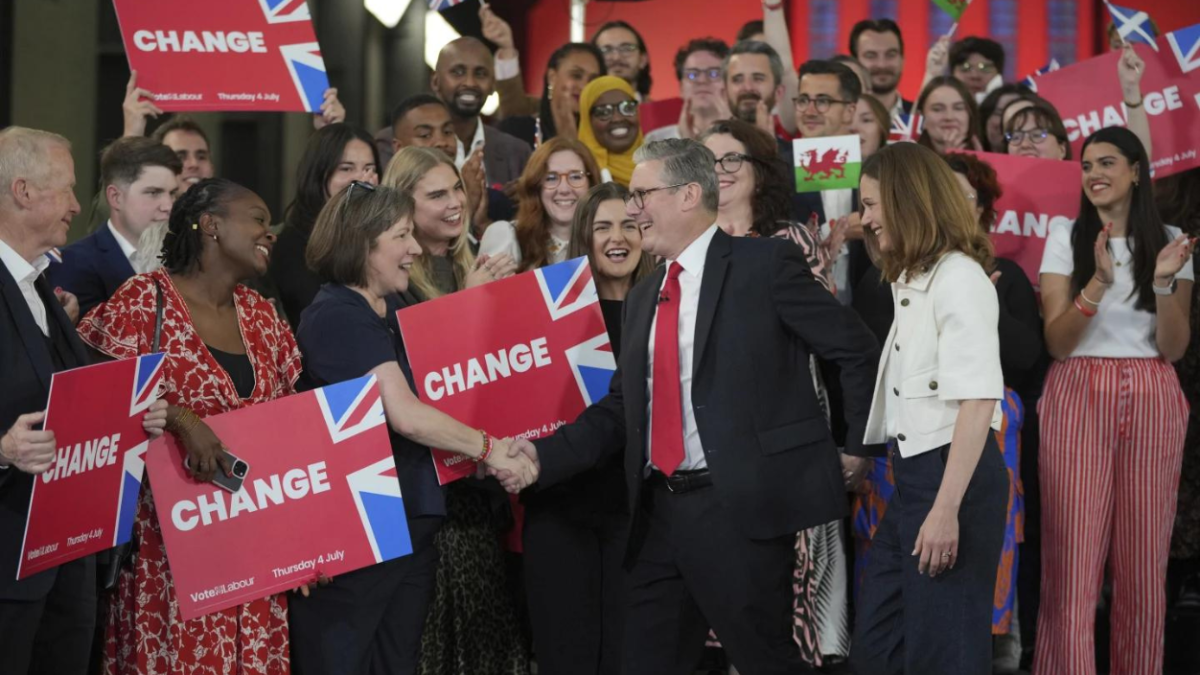

The amendment passed in September after first being introduced in February, then part of “Plan C”, a collection of constitutional reforms. In June, the MORENA party, which AMLO represents, won a legislative supermajority in the elections, and AMLO’s chosen successor Claudia Sheinbaum won the presidency. Ultimately, the judicial reform had the backing it needed to pass in September in the Chamber of Deputies with a final vote of 357 to 130 and in the Senate with a final vote of 86 to 41.

However, the passing of the amendment was not without its difficulties. Protestors stormed the Senate Chamber on September 10, for example, and all opposition legislators boycotted the constitutional declaration on the 13th. Despite AMLO’s belief that the judicial reform will prevent corruption, there are many who claim the opposite: that the reform is actually threatening democracy.

One argument is that the popular election of judges will politicize the judiciary, which is supposed to be fair and impartial. Voters may choose judges that align more closely with their ideologies regardless of the qualifications of the candidates. These political implications could lead to a lack of judicial independence, since the judges directly benefit from political and public opinions. It could even become more difficult for the judiciary to check the presidency, which is an important characteristic of a democracy. This is certainly a concern for the long term.

There are short term consequences, too. The first judicial elections have not yet occurred, and it’s possible that many of the sitting judges will be replaced. A mass removal of judges could threaten the stability of Mexico’s judiciary in the immediate future. In addition, the reform could lead to violation of parts of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which is set to be reviewed in 2026. Trade disputes, diplomatic tensions, and economic problems could all arise due to uncertainty regarding judicial transparency.

Mexico’s first ever judicial elections are set for June 1. Until then, all we can do is speculate about the potential impacts of this new reform – and whether it will ultimately benefit or hurt the nation.