I was reading a Washington Post article titled “I’m a brown immigrant. I visited Marjorie Taylor Greene’s district. Ready?” Naturally, once I finished the article, I scrolled down to perhaps the most interesting part of any article or post: the comments section. I scoured through the hundred comments all seeming to say the same thing, “People were nice to you? They must not have been Republicans then.” A direct quote from one user states, “I often can’t square the fact that someone can be both likeable and vote Republican.”

A Republican who is not a raging racist? Impossible.

Similarly, I read a Fox News article detailing an instance when Democrat officials allegedly violated the right to freedom of speech during a debate about a transgender bill. The comments shouted one message, “Democrats hate freedom of speech.” Taking it one step further, one user comments, “If [the Democrats] have to silence you then they’ll do that. If they have to jail you then they’ll do that. Whatever it takes. No ethics, morals or even law abiding.”

An ethical Democrat who respects the Constitution? Well, pigs must be flying, too, then.

Pro-choice? Murderer. Pro-life? Misogynist.

Pro-gun? Murderer. Anti-gun? Anti-self defense.

The common theme? The other political party is immoral. American political parties have become so inextricably linked with morals that reaching across party lines has become increasingly impossible. This thought process is known as moralism. Moralism involves an over emphasis on morality and can also involve ascribing certain moral traits to a person.

When it comes to politics, this means that every political issue becomes a moral one, deepening divides and driving Americans further away from compromise. Political science professor Kristin Garrett writes, “People who hold strong moral convictions want greater social and physical distance from, they show greater intolerance towards, and they show greater willingness to discriminate against those who hold conflicting views.” She goes on to say, “They come to view their party and its supporters as fundamentally good and the other party and its adherents as fundamentally bad.”

When viewed through this lens, the polarization of current politics makes sense. If the other party is “fundamentally bad,” how can one compromise with immorality? Agreeing with the other party in any capacity feels like moving away from one’s own morals, an idea abhorrent to most Americans.

However, this is not inherently a bad thing. There are certain platforms and ideas on both sides that are immoral, regardless of one’s political views, and it is good to fight against it. The problem lies when this idea seeps into every crevice of a party’s platforms and ideologies. The economy is not an inherently moral issue. Immigration is not inherently moral. Americans have made them so.

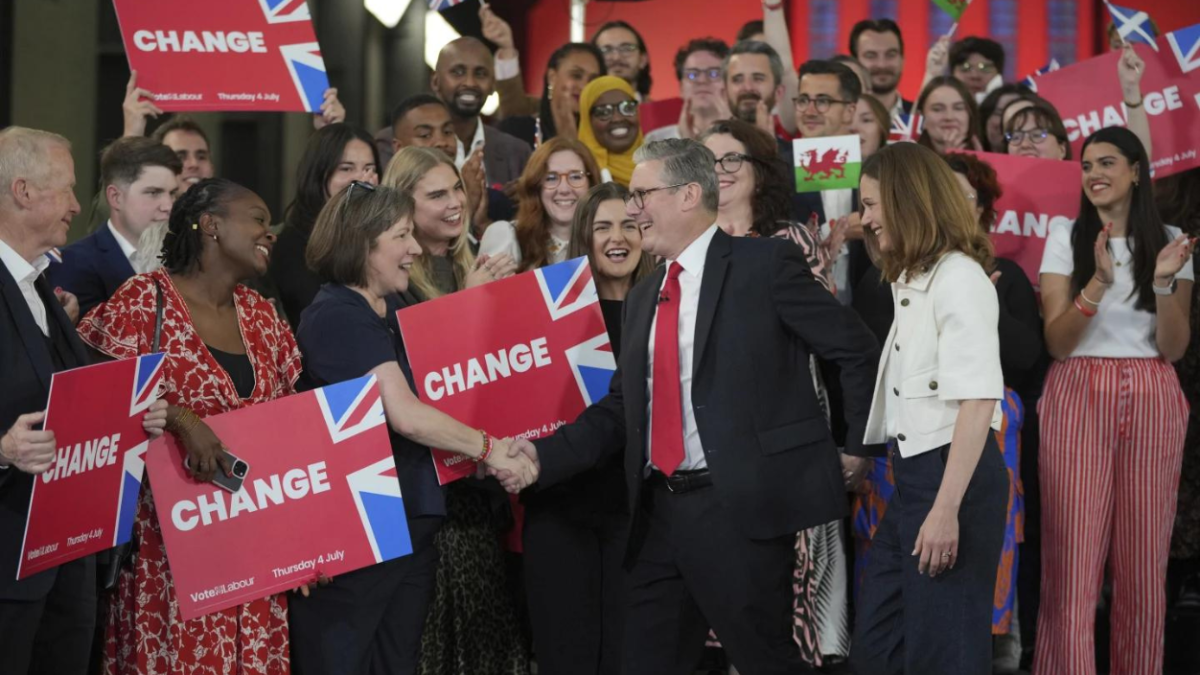

Agreeing with the opposite party does not make a person immoral. Being a member of a certain party does not make a person evil. So, in a time of ever increasing divide, reach out and shake hands with the opposite side. It does not make you any less of a good person.